Kahle Markierung wie bei einem Buschhasen

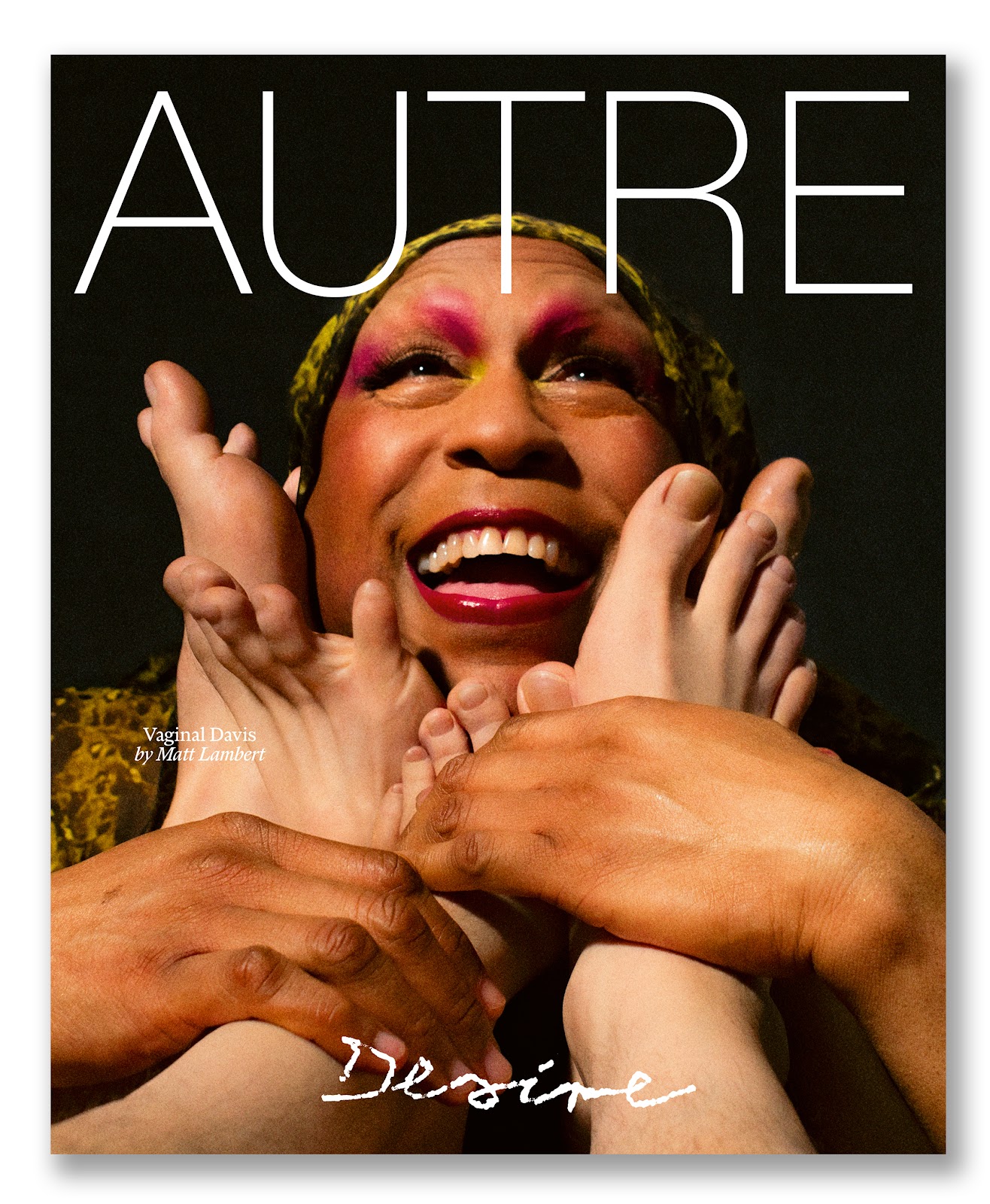

Vaginal Davis fan fiction is spiraling to new heights. This one brought to you via Love Camel in London:

I found the manuscript on the Piccadilly Line between Leicester Square and Cockfosters, one late evening. The carriage was empty except for a man in a velvet suit playing a theremin made of bones. He said to the Camel, “She left it for you” and gave me a shoebox covered in nail polish. Inside there was an unpublished manuscript, hand-labeled in looping cursive—“The Unexpurgated Life of Vaginal Davis.”

The pages smelled faintly of pupusa and Xerox toner. As I started to read the first pages, the carriage began to fill with the distant sound of Cholita! and voracious shrimping. When I looked up, the man and the theremin were gone. Only the manuscript remained—and a Los Angeles bus ticket tucked inside the final page, dated 1992.

The pages smelled faintly of pupusa and Xerox toner. As I started to read the first pages, the carriage began to fill with the distant sound of Cholita! and voracious shrimping. When I looked up, the man and the theremin were gone. Only the manuscript remained—and a Los Angeles bus ticket tucked inside the final page, dated 1992.

*

Delicious Learns to Drive

Los Angeles, 1977

Delicious Sanders was sixteen years old and already a legend on her block, though mostly for falling off her roller skates while holding a trumpet.

Mary Magdalene wasn’t a woman to half-do anything. She believed in astrology, good gospel music, and raising her daughter with what she called “Afro-clarity.” To her, that meant confidence rooted in community and culture. Delicious had been named after her favorite word in the English language, and she reminded her often: "Your name is a blessing, baby. Makes people hungry for who you are."

By summer 1977, it was time. Time for Delicious to learn to drive. But not from just anybody. No, Mary Magdalene mailed a letter, typed on her trusty Olivetti and spritzed with her signature sandalwood perfume, addressed simply to:

Mr. Stevie Wonder, Music Man, Los Angeles, CA

And somehow, impossibly, three weeks later, a reply came. A phone call, actually. From a woman who introduced herself only as "Claudette, Stevie's vibe manager." Stevie had agreed, out of admiration for Mary Magdalene's poetic request, to meet Delicious and discuss some "alternative vehicular instruction."

Three weeks later, a glossy black Lincoln Continental glided down the block like it was skating on Marvin Gaye. Out stepped Stevie, in a purple satin tracksuit, smiling like the sun was an old friend. “I hear someone needs to learn how to drive,” he said, hands wide.

Delicious blinked. “Mommy,” she whispered, “I thought Stevie Wonder was... blind?”

Mary Magdalene waved it off like smoke. “Baby, he doesn’t need to see the road. He feels it. That’s called vision.”

And so it began.

Each Tuesday and Thursday, a matte black Lincoln Continental pulled up in front of their home like it belonged in a blaxploitation film. Inside sat Stevie, clad in velvet and serenity, the car driven by a silent cousin named Willard who only wore mirrored shades.

Delicious and Stevie sat in the driveway. Stevie, ever poetic, never touched the wheel. Instead, he talked. About flow. About rhythm. About how a real driver listens to the engine like it’s a jazz quartet. “Every car’s got its own tempo, Delicious,” he’d say, tapping the dashboard like it was a conga drum. “Don’t drive it—collaborate with it.”

Sometimes they’d cruise slowly through the neighborhood, Delicious behind the wheel and Stevie singing “Sir Duke” from the passenger seat, waving at kids on bikes and barking dogs like a presidential motorcade. Stevie insisted on parallel parking by ear. “Click-click... stop. You hear that rhythm? That’s the curb saying hello.”

They never went to Santa Monica or the Sunset Strip. No. Stevie took Delicious to the forgotten places:

To the train yards near the Crenshaw Slauson industrial corridor, where graffiti bloomed on every wall and the smell of old diesel mingled with taco trucks and blooming sagebrush.

To the Baldwin Hills oil fields, where derricks pumped rhythmically against the sky like slow-motion dancers.

To the wide boulevards behind Jefferson Park, where kids bounced basketballs under jacaranda trees and old men sat on folding chairs playing dominos and telling lies about women from back East.

Delicious didn’t learn to drive in the traditional sense. Stevie never touched the wheel. He talked instead. About vibration. About balance. About learning how to feel a turn in your kidneys and hear an engine like it was improvising bebop.

"Cars," Stevie said, tapping his temple, "are just extensions of your groove. You don’t steer 'em. You collaborate with 'em."

Delicious tried. She really did. But every lesson ended the same. One time, she clipped a dumpster behind an auto parts store in Watts. Another time, she nearly drove straight into the Ballona Creek, distracted by a particularly bold crow.

Once, on a hot August day, they tried to merge onto La Cienega from a side street in Culver City. Delicious panicked, turned the wrong way, and landed them in a Ralphs parking lot where a boy from her school worked bagging groceries. He waved, then laughed for three full minutes.

Finally, Stevie put his hand gently on Delicious' arm and said, "Maybe you're not meant to drive cars. Maybe you drive ideas instead."

Delicious blinked.

"I can do that?"

"You just have to stop trying to steer."

Mary Magdalene was disappointed, of course. But only for an hour. Then she sat her down, handed her a mirror, and said, "You may not drive, but baby, you arrive."

By the early '80s, Delicious had reinvented herself as a gender-bending drag phenomenon known only as Vaginal Davis. She stormed stages from Silver Lake dive bars to warehouse balls in East L.A., delivering midnight sermons about liberation, beauty, and failure. She never drove a car again, but her presence could stop traffic.

They still talk about her in dressing rooms and dim hallways of Hollywood nightclubs—the queen who couldn’t parallel park, but who navigated the chaos of life with nothing but a wig, an attitude for shrimping, and the groove Stevie gave her.

Delicious Learns to Drive

Los Angeles, 1977

Delicious Sanders was sixteen years old and already a legend on her block, though mostly for falling off her roller skates while holding a trumpet.

Mary Magdalene wasn’t a woman to half-do anything. She believed in astrology, good gospel music, and raising her daughter with what she called “Afro-clarity.” To her, that meant confidence rooted in community and culture. Delicious had been named after her favorite word in the English language, and she reminded her often: "Your name is a blessing, baby. Makes people hungry for who you are."

By summer 1977, it was time. Time for Delicious to learn to drive. But not from just anybody. No, Mary Magdalene mailed a letter, typed on her trusty Olivetti and spritzed with her signature sandalwood perfume, addressed simply to:

Mr. Stevie Wonder, Music Man, Los Angeles, CA

And somehow, impossibly, three weeks later, a reply came. A phone call, actually. From a woman who introduced herself only as "Claudette, Stevie's vibe manager." Stevie had agreed, out of admiration for Mary Magdalene's poetic request, to meet Delicious and discuss some "alternative vehicular instruction."

Three weeks later, a glossy black Lincoln Continental glided down the block like it was skating on Marvin Gaye. Out stepped Stevie, in a purple satin tracksuit, smiling like the sun was an old friend. “I hear someone needs to learn how to drive,” he said, hands wide.

Delicious blinked. “Mommy,” she whispered, “I thought Stevie Wonder was... blind?”

Mary Magdalene waved it off like smoke. “Baby, he doesn’t need to see the road. He feels it. That’s called vision.”

And so it began.

Each Tuesday and Thursday, a matte black Lincoln Continental pulled up in front of their home like it belonged in a blaxploitation film. Inside sat Stevie, clad in velvet and serenity, the car driven by a silent cousin named Willard who only wore mirrored shades.

Delicious and Stevie sat in the driveway. Stevie, ever poetic, never touched the wheel. Instead, he talked. About flow. About rhythm. About how a real driver listens to the engine like it’s a jazz quartet. “Every car’s got its own tempo, Delicious,” he’d say, tapping the dashboard like it was a conga drum. “Don’t drive it—collaborate with it.”

Sometimes they’d cruise slowly through the neighborhood, Delicious behind the wheel and Stevie singing “Sir Duke” from the passenger seat, waving at kids on bikes and barking dogs like a presidential motorcade. Stevie insisted on parallel parking by ear. “Click-click... stop. You hear that rhythm? That’s the curb saying hello.”

They never went to Santa Monica or the Sunset Strip. No. Stevie took Delicious to the forgotten places:

To the train yards near the Crenshaw Slauson industrial corridor, where graffiti bloomed on every wall and the smell of old diesel mingled with taco trucks and blooming sagebrush.

To the Baldwin Hills oil fields, where derricks pumped rhythmically against the sky like slow-motion dancers.

To the wide boulevards behind Jefferson Park, where kids bounced basketballs under jacaranda trees and old men sat on folding chairs playing dominos and telling lies about women from back East.

Delicious didn’t learn to drive in the traditional sense. Stevie never touched the wheel. He talked instead. About vibration. About balance. About learning how to feel a turn in your kidneys and hear an engine like it was improvising bebop.

"Cars," Stevie said, tapping his temple, "are just extensions of your groove. You don’t steer 'em. You collaborate with 'em."

Delicious tried. She really did. But every lesson ended the same. One time, she clipped a dumpster behind an auto parts store in Watts. Another time, she nearly drove straight into the Ballona Creek, distracted by a particularly bold crow.

Once, on a hot August day, they tried to merge onto La Cienega from a side street in Culver City. Delicious panicked, turned the wrong way, and landed them in a Ralphs parking lot where a boy from her school worked bagging groceries. He waved, then laughed for three full minutes.

Finally, Stevie put his hand gently on Delicious' arm and said, "Maybe you're not meant to drive cars. Maybe you drive ideas instead."

Delicious blinked.

"I can do that?"

"You just have to stop trying to steer."

Mary Magdalene was disappointed, of course. But only for an hour. Then she sat her down, handed her a mirror, and said, "You may not drive, but baby, you arrive."

By the early '80s, Delicious had reinvented herself as a gender-bending drag phenomenon known only as Vaginal Davis. She stormed stages from Silver Lake dive bars to warehouse balls in East L.A., delivering midnight sermons about liberation, beauty, and failure. She never drove a car again, but her presence could stop traffic.

They still talk about her in dressing rooms and dim hallways of Hollywood nightclubs—the queen who couldn’t parallel park, but who navigated the chaos of life with nothing but a wig, an attitude for shrimping, and the groove Stevie gave her.